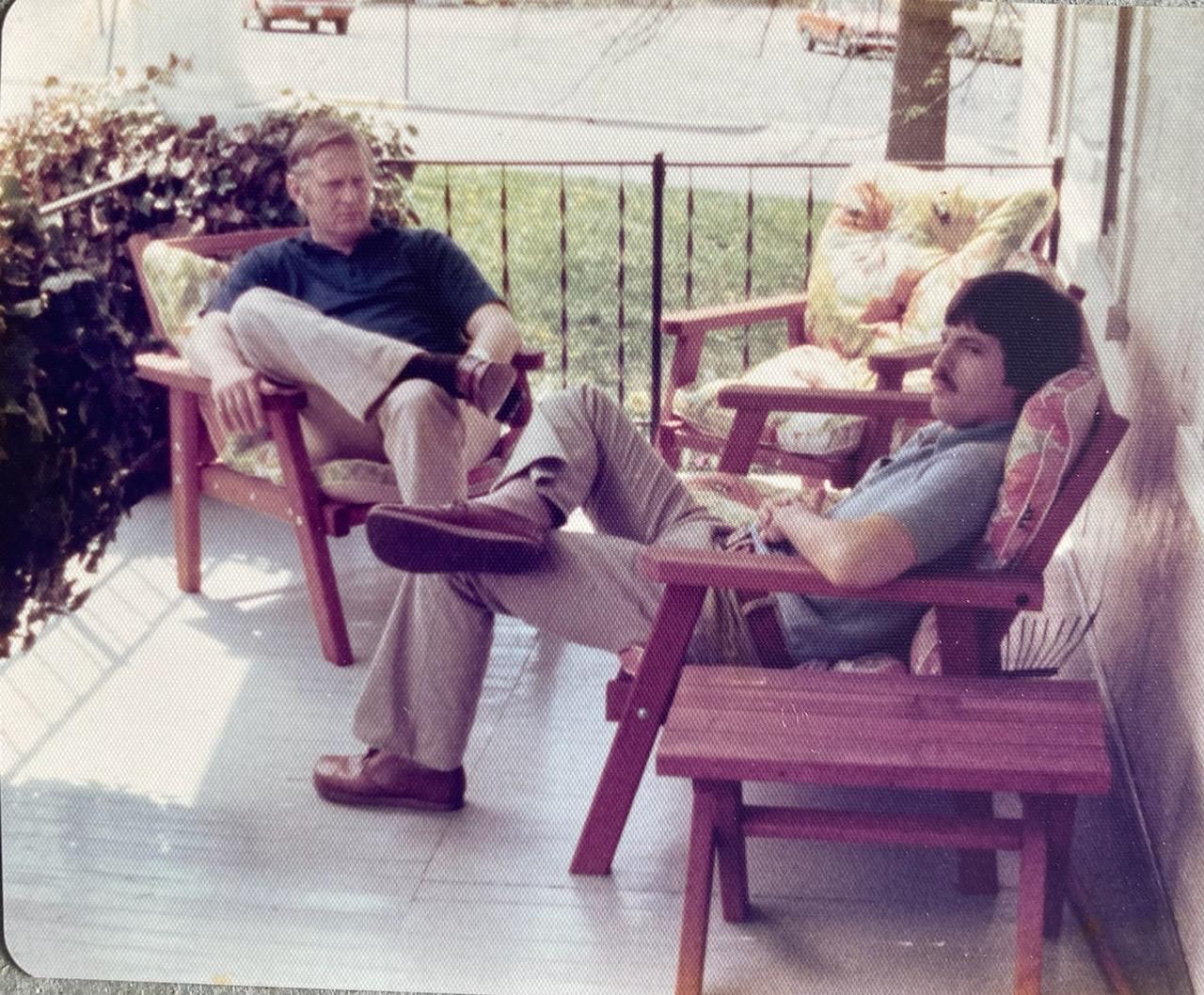

Hello, poetry people. Welcome to my first Poetry Path blog. I plan to post once a week, focusing mostly on writing verse. Today I’m adding a picture taken long ago, partly to prove that I haven’t always been older than dirt but also because I want you to consider the long and often crooked path that any poet is likely to walk through a lifetime.

The photo shows me at about age 24, sitting on my grandparents’ porch, talking with my uncle, Jack Kidd. Jack was a great influence on me. He was the finest literature scholar I’ve ever known and before becoming a printer had been a college English professor. When the photo was taken, I was in my first year of teaching English at James Madison University. Jack had written poetry since before I was born, and I was by training a poet, having gone through a master of fine arts program in creative writing. I’ve written a great deal since that day, and I’ve lived and experienced a great deal.

The year of the photo was 1977. I’m wearing “earth shoes,” a footwear fad that lasted a short time. The soles of earth shoes were backward, with the thickest part in the front and the thinnest part at the heel. Anyone wearing such shoes seemed to be walking slightly uphill all the time. I don’t remember why I thought that was a good idea. Also, notice how wide my belt is. You should have seen the ties I wore to class. That was the 70s. But, as singer-musician-songwriter Ian Anderson of the band Jethro Tull wrote, “Life’s a long road.”

Which brings me to what this is really about—the poet’s path. In the 1980s I met a poet named Marilou Awiakta, whose last name in Cherokee means “eye of the deer.” Marilou made a casual comment about my being on the poet’s path. She didn’t elaborate. Over time, my mind did that.

I came to see the poet’s path as a narrow trail that everyone who has ever written a poem, no matter how amateurish, has taken at least one step on. It’s the same path that Shakepeare walked. Sappho, Socrates, Whitman, Dickinson, Eliot, Plath, Levertov and Nemerov all walked it. They walked it a long way and found their place in something like a poets’ hall of fame. I walk it, all of the students I taught in poetry writing classes walked it, and some of them are still walking it. If you write verse, have written verse or are about to write verse, you’re on it too. Since I met Marilou Awiakta, I have never taught a poetry composition class without explaining the poet’s path at the first meeting and continually bringing it up throughout the semester. It became the central concept on which I hung the course’s curriculum.

Let’s take time out for a little background. After teaching at JMU for two years, I returned to graduate school, once again in creative writing. Then, because I felt the need to be a latter-day renaissance man (which sounds better than saying I wanted to do several things at one time), I hung around my hometown in order to make use of a family farm. I got on at a local community college, and there I taught until I retired, writing when I could and first growing Christmas trees and later, with my wife, breeding Gypsy horses. I retired from teaching at the end of 2018, and for the past year my wife and I have lived separately, she with the horses and I with my keyboard. Life is indeed a long and often surprising road, and poetry can be too.

People certainly can write poetry without ever considering that they’re on any path other than their own, but I think the experience is much richer if we poets see ourselves as being on a path together, the poet’s path. When people are on a path together, they help one another. “Watch out for this low-hanging branch,” a walker might call to the person following him. “There’s a hornet nest hanging from it.” (Translation: “Don’t bother sending your poems to that magazine. Its editor’s an imbecile.”) Or, “Do you have any water to spare?” a person might ask the hiker in front of him, who says, “I’m really sorry. I just finished my bottle.” (Translation: “Have you read any poems by Brad Burkholder?” “Only one, and that was enough.”) See?

The concept of the poet’s path is the great equalizer. We might all be at different points along the path, but we are all on it. We have something in common with each other that we don’t have in common with other people. We are a kind of community. One person has spent 25 years on the path. Another has spent 25 days on it. That doesn’t make one person a better poet. It makes one person a more experienced poet. Where the new poet is, the more experienced poet has been. Where the more experienced poet is, the new poet will be in time. The satisfaction of being a poet is in learning the craft and growing in it. Another satisfaction lies in helping other poets move along the path. There should be no competition, only cooperation.

I made the poet’s path a rule in my classes. The students bought into it. I never heard a student make a nasty remark about another student’s work—and we spent most of our class time talking about, critiquing, poems the students had written. As for myself, when a student brought in a poem showing a significant lack of experience, remembering the poet’s path, I’d often say something like I remember when I was about where you are and wrote poems very similar to this one, and I think that in a couple of years you’ll likely make a different choice, maybe like this . . . An approach like that makes apprentice writers feel understood, helped and appreciated rather than insulted and discouraged. I myself have been made to feel bad in writers’ groups. It’s destructive and unnecessary. And it never happens when the members of the group see themselves as all being travelers on the same path.

Being on the poet’s path together can lead individuals to great discoveries. Sometime in the 1990s I had a class that had more trouble than most in hearing the rhythms of the English language. Blank verse, iambic tetrameter and such weren’t going to happen, yet I wanted the students to get some sort of practice using formal structures. I came up with an idea and made an assignment based on it. When we met the next week, everyone would have a poem written to my exact specifications. I won’t say there wasn’t a little griping. One young lady made this announcement: “Okay, we’ll do it, but since we’re all in this together, you have to do it too.” A perfect—and amusing—use of the poet’s path to make the teacher suffer along with his students. Laughing, I accepted the assignment, and a week later I had a poem that would push me a good distance farther down the path.

That poem and what came of it will be the subject of my next blog. By now I’ve written dozens of poems in that form. I’ll share the poem, explain how to write such poems, tell you what the form is called, and dare you to write one and send it to me. (And just in case you’ve spent too much time around the Grammar Lady and you’re thinking it should be the poets’ path instead of the poet’s path, I’ll tell you why I like the apostrophe inside the s.)

Please come back. I’d like you to join me on the path. And please think about signing up for an occasional email. I won’t bother you often, only when there’s something good.

Take care.